The most exciting event at WPBO’s waterbird count this week has been the big loon push. This is, for me, a favorite part of spring. The loons are the vanguards of the opening migration floodgates. They signal the onset of a month that passes — like the white wedge on the outer limits of a Bonaparte’s Gull’s primaries — in a beautiful flash. It’s thrilling, too, to imagine so many Common Loons journeying to remote lakes in the Canadian Shield, the red-throateds all the way north to the tundra of the coastal plain.

WPBO’s loon flight is fun because of its challenge element, too. The loon flight travels through a much broader swath of sky and horizon than many of our other flights. Where most waterbirds seem more strongly bound to water, preferring to hug the lines of Superior, strong-flying loons (which have been tracked migrating at 70mph!) are prone to just cut across land from Whitefish Bay to Lake Superior. To catch more of these loons shortcutting the tip, my scope scans become 360 fairly frantic degrees. I turn circles on the beach, searching a sky that’s full of loons streaming north. They travel alone, in pairs, or in widely — but aesthetically — spaced flocks strung out across the sky like constellations. And even in the brutality of trying to keep up with them all, it’s impossible not to appreciate the beauty of this happening.

I also love that there is a “local loon” that spends its days on the bay. It is very territorial, crying “stay-away!” calls at most of the loons passing overhead. For the springs I’ve spent here, this loon has been one of my most useful count assistants: it has helped me detect many loons streaking directly over the shack (the ones I am most prone to miss), and when my sleep-deprived eyes begin to ache during the bluebird afternoons we’ve been having, I can rely on this loon ally to aid me through those last brutal hours. Unlike me, it never mistakes loons for cormorants. One time, I thought it did, for the loon on the bay called and I looked up to see a cormorant but not a loon. “Hah, you do that too,” I thought happily. Then, a few seconds later, a very high Red-throated Loon passed over too.

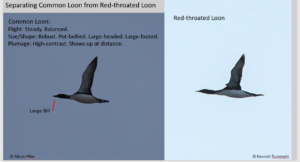

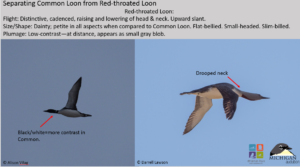

Separating Common and Red-throated Loons flying at the distances we expect to see them here is a process built from discerning subtleties. It requires putting trust in wingbeat and structure more than plumage. If the feet seem small, the belly flat, the bird is a good candidate for red-throated. When it draws near, and we can see the head, petite, is raised and lowered almost rhythmically, we are confident in our red-throated identification. But what if the bird is large-footed and amply paunched — indicating Common Loon — but is also moving its head and neck around like the red-throated before? It’s a Common Loon that’s looking around as it flies. At the waterbird count, we rarely get a perfect look, a perfect bird that aligns completely with the identification tells we’ve read about in our field guides. We go by feel out there, and those feelings for me are backed up by having witnessed, over my cumulative seasons, tens of thousands of migrating loons on Lake Superior.

It’s not often that I have visitors to the count who find the waterbird count as magical as I do — or commit for as long as I do, either. For the last week, I’ve shared the bulk of the count hours with a visitor who wanted to learn loon-in-flight identification. And it’s been really nice to share this space and some truly beautiful migration moments with someone who digs the waterbird flight as I do. I’m also grateful for this visitor because he’s helped me develop a diplomatic term for the periods of time when waterbird migration is too heavy for me to allot much awareness to visitor interaction. It’s called “Alison’s Focus Time.” And this idea is something I would like prospective visitors to keep in their minds. It is important to me that the Point be shared well with those who want to experience it, and I am often in a position to do that. But sometimes, the flight gets so busy that it demands undivided attention. If I come off as unfriendly or aloof, it’s only because I’m trying my best to keep up with the myriad birds winging their way north.

During the dates encompassed in this blog, I’ve observed 1,096 Common Loons and 139 Red-throated Loons. Red-necked Grebes have been numerous, too, with 528 being tallied in the period. Other highlights have included Iceland, Glaucous, and Lesser Black-backed Gulls and Trumpeter (in feature photo) and Tundra Swans. As always, thank you for reading!

~ Alison Világ

2022 Spring Waterbird Counter

Featured photo: Trumpeter Swans. Photo by Alison Világ

Support WPBO’s Research During Birdathon on May 28

Our skilled team of bird counters and volunteers at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory will set out on a mission to count as many bird species as possible in one day on May 28, 2022, as part of an annual fundraising event supporting the amazing work happening at WPBO! In 2021, a whopping 152 species were counted and the event brought in $6,826.65! Let’s hope this year is just as successful.

This is where you come in! Because our work is 100% donor-funded, Birdathon provides all of our supporters with an opportunity to make a significant impact on our work by making a pledge or direct donation to Birdathon (even after the event). Any amount is helpful, but have some fun with it and consider letting your donation or pledge be inspired by a per-species amount.

Learn more about Birdathon and find links to donate at wpbo.org/birdathon.

Thank you so much to everyone who supports the work being done at WPBO!